The Future isn’t what it used to be: Open Education at a Crossroads OER24 keynote resources3/4/2024 At the recent OER24 conference in Cork, Ireland, Catherine Cronin and I had the great honour of giving a joint keynote, in the company of the other keynoter, the inimitable Rajiv Jhangiani. In addition, we were inspired by the range and depth of work shared by so many in the international open education community who presented and participated in the conference. We have many thoughts and reflections mulling away. For now, we are sharing resources from our keynote, The Future isn’t what it used to be: Open Education at a Crossroads. Slides: We presented the keynote using a slide deck with few words, informative images, and some wonderful abstract and alternative visuals (we are not boasting, thanks go to the excellent artists). The slides are at https://bit.ly/oer24-crossroads. Keynote essay: We also wrote up the keynote as an essay. It is not quite a transcript as it is halfway between talking and writing, including all of the references we used. You can find it here. Video recording: Thanks to the conference organisers, ALT and Munster Technological University, the keynotes were also recorded. Ours can be accessed here (our talk starts at 23:30). Resource list: During our talk, we linked to a list of critical tech organisations and initiatives which we have been keeping. We thought this might be useful to others, so have created a shared and editable spreadsheet of critical tech organisations and initiatives here, which everyone is invited to use and/or add to. Participant responses: Finally, during our keynote, we asked everyone in the room two questions. Near the start of our keynote, we asked: “What do you think of when you hear “open education?”. The responses from participants are here, in the form of a word cloud –– largely positive and hopeful words. Q1: What do you think of when you hear “open education”? Q2: What could we do right now?

The second question we posed, right at the end of our talk, was: “What could we, as this community – this conference group – do right now?”. With just a few minutes to collect responses, it was encouraging to receive over 90 immediate suggestions. We have clustered these suggestions into the following eight themes, for ease of sharing:

1. Take action, make plans

7. Challenge existing power structures; work towards justice

0 Comments

Stop making sense? Hopefully not. No, never! Stop making sense of, stop sense making? Not as long as my mind allows it. Recently, Catherine and I were guests on Bryan Alexander’s Future Trends Forum where Bryan’s opening question as always, was to ask what we were going to be doing in the year ahead. I responded by listing what I would not be doing- running a centre, leading a project, being at the helm of anything. But one thing I wouldn’t be doing is to stop sense making.

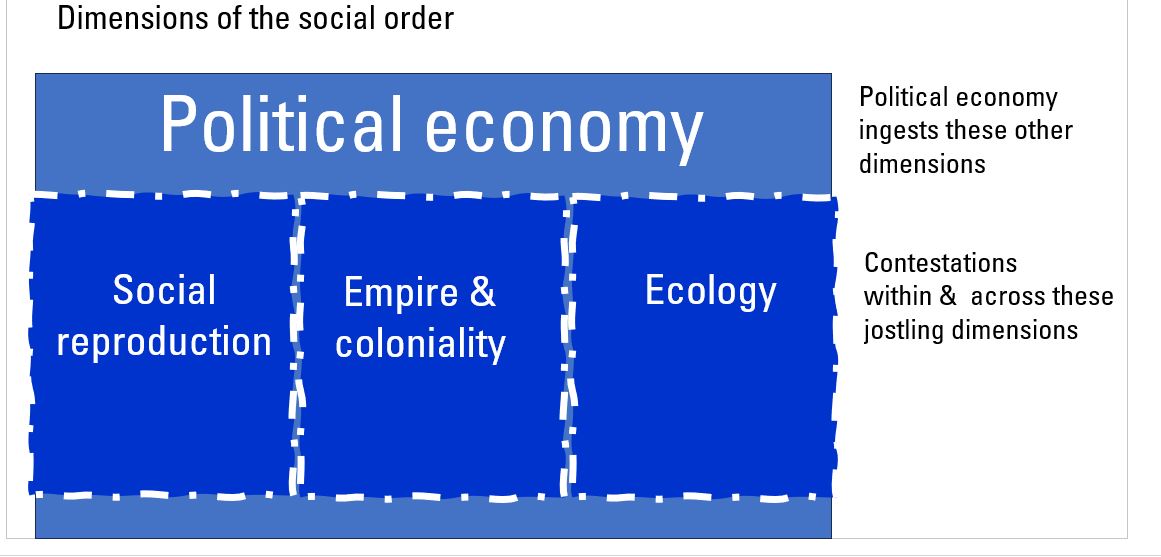

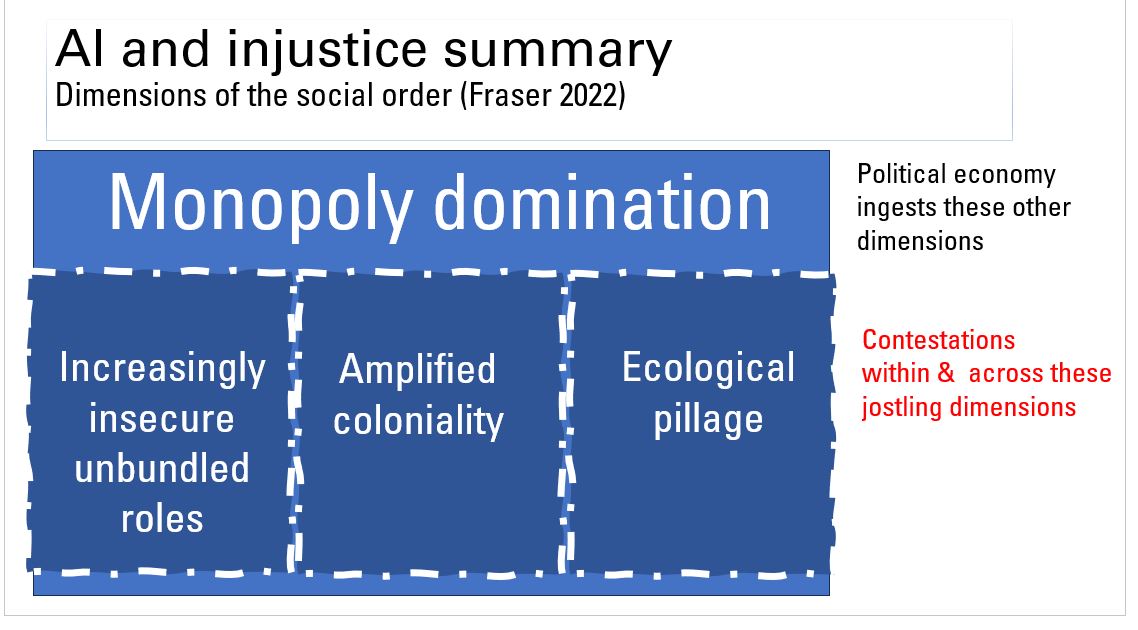

South African universities have a compulsory retirement age, and that is a positive requirement in a shrinking sector. Of course, the assumption is that older people retiring will bring younger people into the system, enabling transformation and innovation. That is surely a good. The risk though, is that expensive permanent senior staff are replaced by younger contracted staff. Who may indeed change the demographics of the sector, but by virtue of their insecure status are in a weaker position to confront and challenge their institutions. The available data supports this: in South Africa the number of all permanent staff has been decreasing over the past few years while the number of contracted academic staff has been growing. So, I am formally retired. Kind of retired. In another, related conversation George S started an important conversation about intergenerational knowledge sharing and solidarity. Because it is not simply a matter of handing over the baton, but of working together to change the sector and society for the better. That one is ongoing, for sure, when there is a very real polycrisis with so much fake news, so much everything-equitable ‘washing’, so much confusion, and so much to be done. This blog began with an update to the About Page and look where it led! *Stop Making Sense of course also dates me to the 1980s concert by Talking Heads. It amuses me that the band’s name was suggested by a friend of the band who picked up a TV Guide and pulled out a style of presentation described as ‘the most mundane and the most informative’. Who would ever have imagined how widespread that style would become online? Writing this also sent me back to listening to Burning Down The House, Life During Wartime, Road To Nowhere…songs that seem both prescient and relevant now. But let me not get too nostalgic for an old American band, whom I am probably getting rose-tinted about because their concert had a great title! Along with many others, I have been mulling on the implications of AI for in/equality, and on the relationship between AI and in/justice. This is something I have spoken about and intend to write up. To answer the question “What does this mean for educators?” has meant standing back and drawing on literature from outside of education. Fraser’s* ideas about cannibal capitalism offered a way a way to frame an extraordinarily complex and entangled set of relationships. The image above shows the framework I have summarised from Fraser's writing, and the image below sums up the situation of AI and injustice succinctly. On the whole, the picture is gloomy. Not surprisingly. But in order to change things, we have to understand them, and this is a set of issues that has purposefully been rendered opaque. As a contribution to change, I try to map them out. As a placeholder, as I haven’t yet managed to write up a narrative, here are the slides I have been using. They are openly licensed so you are welcome to use them, with attribution and the same licence. It is of course only a small beginning. Hopefully, the slides are relatively self-explanatory. Please do contact me if they are not. This is very much a work in progress! * Fraser, N (2022) Cannibal Capitalism Verso Books

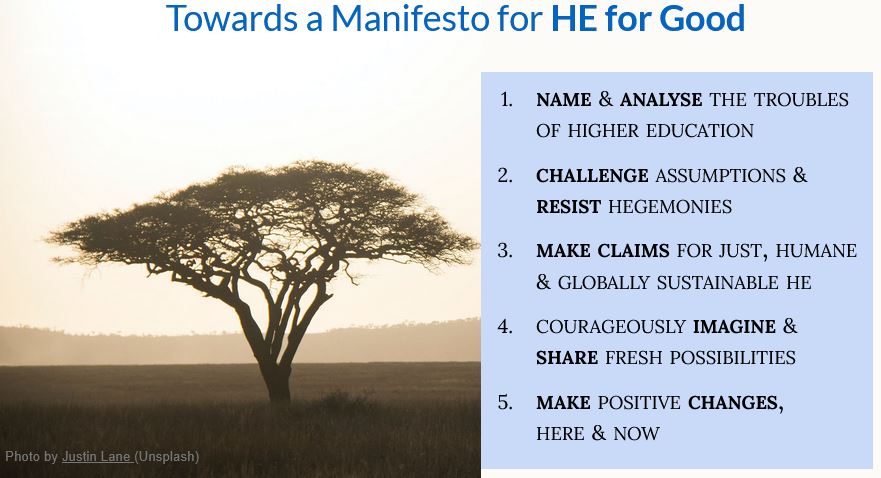

After more than two years of work, our book Higher Education for Good, is published. It is a wonderful, exciting, satisfying and celebratory moment for co-editor Catherine Cronin, myself, and the 71 authors from all over the world, as well as for the fabulous Open Book Publishers.

I have so much to say but right now, the main things is YOOOOOHOOOO and, of course, also, WHEW! Catherine and I have written about the principles and process of the book project and will write more about the content of the 27 chapters, and of course about the tenets towards a manifesto for HE For Good. There is also more to say about how many people and roles are involved in making a book like this. It is really pleasing that the book is published during Open Access Week, an issue close to our hearts. I spoke about why this matters so much in this short clip for The Academy of Science, whose Chairperson, Prof Jonathan Jansen, wrote the Foreword for the book. The realities of academic publishing, the variations of open access publishing (and its attendant open washing), those are also definitely the subject of a future blog posting. And, perhaps most importantly, it is not only higher education that needs help and hope right now. Given the heartbreaking events happening in the world, there is more need than ever for hope. As Catherine and I wrote in our chapter...... Hope is firmly rooted in the belief that it is never too late. Hope is practical. It means taking action, being disciplined, making plans. Hope is impractical. It means dreaming, being undisciplined, being open-ended. Hope is strengthened when practised in solidarity with others. It means building and strengthening alliances, coalitions, communities. Hope is contested and contradictory. And yet whatever its form, it is essential. Without hope, there would be no future worth living by Laura Czerniewicz and Catherine Cronin Cross-posted at http://catherinecronin.net/reflecting/he4good-curating Image: Book in Community, created with Stable Diffusion

Higher Education for Good: Teaching and Learning Futures is a book (soon to be published) that offers ways of thinking, conceptualising and creating possibilities for (re)making higher education, focusing on futures that foreground inclusion, equity, social justice, care and sustainability. In this post, we describe how we set out to create and curate the book as a cohesive collection, enacting the editorial principles of heterogeneity, care, and community which we explored in our previous blog post. Conceptualising and curating the collection, it was important to us that the book not be simply a bundle of chapters with an overarching theme, or a publishing spot for existing chapters on tangential topics, in need of a home. Catherine and I spent a good six months in deep discussion about our vision, our hopes, and our ideas for bringing them to life, before publishing our call for proposals. With the intention of a diverse, global authorship for the book, we worked hard to share the call for proposals far and wide. This required several “waves” of sharing and invitations. Initially, we shared with people, organisations and networks with whom we were already familiar – publishing on our blogs and social media, always using the hashtag #HE4Good. After this, we searched for names and contact details for regional and national organisations and projects in relevant areas, speakers at relevant conferences, and UNESCO chairs in higher education-related areas, inviting them to share the CfP and perhaps to submit a proposal. We also took the opportunity to present our ideas, through for example GO-GN, a network with international reach. And we reached out personally to invite individuals whose perspectives and ideas we found valuable and which aligned with our vision. The required proposal was longer than usual (about 1000 words) and required a clear alignment with the book’s themes. To our delight, within two months we had received nearly 100 proposals. After a thorough review (and much more discussion – this book has been an ongoing discussion!), we invited the authors of 32 proposals to submit chapters for HE4Good. While awaiting proposals, we created a set of criteria by which to assess each. Firstly, each proposal was assessed to see how well it met the details outlined in the call; this included exploring key principles which speak to “good” and including a focus on teaching and learning. Secondly, we prioritised proposals indicating creative approaches. Where specific projects were described, we prioritised proposals that considered projects in wider contexts and as catalysts for broader issues. Where proposals were based on individual reflections, we prioritised those that were linked to broader issues, specifically, how to create better futures. Even with this set of criteria, we found that there were more proposals than we could accommodate in the book. Thus, in a final, difficult round of selection, we considered the book as a whole, prioritising diversity of geographic location, HE context, and authorship, so that the book would represent as wide a range of standpoints and HE contexts as possible. In all communications with authors, from the start we made it clear that we intended the project deadlines to be real. In order for the book to come out within a reasonable timeframe, both we and the authors had to do our best to stick to deadlines. Once authors were writing, we turned our attention to building personal, collaborative partnerships with all authors. Whether authors had been known to us previously or not, and whatever each author’s position, location or circumstances, we sought to support each author so that their voice and chapter would be the best it could be. At the same time, we also sought to create a community of authors. This was important for two reasons. Firstly, it would lead to a more coherent book, with echoes and themes running across chapters. Of course, we could do some of this work as editors, but it is more authentic when authors speak directly to one another. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, this book has never been simply a book. For us it has been a contribution to coalition-building, for making connections between dispersed voices, too often isolated from one another, and all sharing deep concerns about the state of higher education. It is not enough to feel or point out the problems, it is essential to explore and create alternatives, and to build momentum towards alternative futures. To begin building such a community, we initially invited the 70+ authors to share their chapter titles, abstracts and contact details, so that these could be shared across the entire author community . We created shareable folders so that authors could share their drafts, if they wished. Several authors made contact with one another this way, to engage in discussion and to share their work as it developed. As we describe in the next blog post, the fact that authors peer reviewed one another’s work made a real difference too. In addition, we organised two online meet-ups at different dates/times, necessary because authors were dispersed globally across nineteen time zones. These provided spaces for getting to know one another, for identifying shared themes and gaps. Building on ideas from authors, we also scheduled two subsequent ‘Drop In and Write’ sessions; while functioning as allocated quiet spaces for writing, these also included opportunities for fruitful discussion. In terms of organising this as an editorial project… yes, it is all time consuming. And yes, there is always more that can be done. And yet. Over the course of twelve months, from acceptance of chapter proposals (February 2022) to submission of the book manuscript to the publisher (February 2023) – and beyond – our vibrant author/editor community has fueled ideas, imaginations and spirits. As editors, we have been continually gratified and humbled at the level of dedication, scholarship and kindness of the HE4Good authors – and look forward to sharing the fruits of this community of scholars when the book is published, openly, in just a few weeks. In the next blog post in this series, we will describe the peer review process with the option of open peer review, as well as the mentoring offered to authors. Thanks to Aras Bozkurt for the following outburst, written in response to his call for comments on the importance of open education at the moment.

In these turbulent times, openness in education is indeed important because its previous incarnations have lost relevance with too often the term itself having been appropriated by the very forces against which it is supposed to stand. Openness in education has also become so all-encompassing a word that it means whatever a speaker or reader wants it to mean, thus lacking consensus and even meaning. In the narrowest sense, openness can simply refer to content being made available under a Creative Commons licence. But in the new era of generative AI, even those licences must, and do, come under scrutiny. When all multimodal content can, and is, mixed and mashed through opaque neural networks and at the click of a button, then machine-read CC licences lose their power both technically and culturally. It is often forgotten that CC licences are a form of copyright; both copyright and the permissions manifest in open licences are urgently and appropriately under review In addition to content, openness in education is often portrayed and viewed as “nice” and “caring”. When so many educators are overburdened, underpaid contractors, their apparent failure to share and care does not indicate lack of caring as individuals, nor are those open practices individual responsibilities. It rather points to failures of educational systems and sectors which are increasingly turning the education sector into an ironically termed “sharing economy”, a gig economy of unbundled services and roles, each squeezing out profits. Broadly speaking, openness in education refers to practices and processes that exist in opposition to the dominant discourses of big tech, platformisation, surveillance and academic metrics systems. This positions openness as a resistance force, an essential role, but limited by being against something rather than for something. Openness in education at this moment in time has to be rearticulated, and in particular considerations of governance and structural forms are priorities. Regulatory frameworks and processes to develop them are boring and not the remit (or interest) of most educators, but without such systemic articulations, sustainable open education will be impossible to achieve. * Image Ian Dolphin https://www.haikudeck.com/oss-benefits-business-presentation-uXH7CLg2VX#slide13 By Laura Czerniewicz and Catherine Cronin Cross posted at http://catherinecronin.net/reflecting/he4good_principles/ In a few months, all being well, we will be preparing to launch the book Higher Education for Good: Teaching and Learning Futures (HE4Good). This open access book, a collection of work by over 70 authors in 18 countries, offers ways of thinking, conceptualising and creating possibilities for (re)making higher education, focusing on futures that foreground inclusion, equity, social justice, care and sustainability. In this liminal space —after completing the bulk of the writing and editing, and before making final changes to the manuscript— we are reflecting on the process of creating the book. Working from an understanding that “the large is a reflection of the small” (brown, 2017), we agreed from the start that each of our decisions about the book’s creation would themselves need to reflect the values of inclusion, equity, social justice, care and sustainability. So, how did this belief translate into practice? This is the first in a series of blog posts in which we’ll reflect on the process of making the book – in other words, what we did (or tried to do) and why. In this first post we outline how the idea for the book arose and describe our process principles. Seeds of an idea In June 2021, when first discussing the ideas for what became HE4Good, we each were working as full-time academics (Catherine in Ireland, Laura in South Africa). Both committed to open education and social justice, we have been colleagues and friends for several years. Mid-2021 saw us navigating the pandemic in our own lives and HE sectors, facilitating teaching and learning alongside our colleagues, supporting teachers and students, and advocating for care and equity as HE practices and systems changed dramatically. We witnessed the escalating use of opaque digital infrastructures and algorithmic decision systems. This left so many of us exhausted and despairing – but never without hope (Czerniewicz et al., 2020). Yet we felt, as Rosie Braidotti (2020) powerfully describes, that we could “extract ourselves from this sad state of affairs, work through the multiple layers of our exhaustion, and co-construct different platforms of becoming”. The book Higher Education for Good was thus conceived as a means to counter despair, resist dominant narratives, and imagine and bring into being better futures for higher education. As we explained in our original call for chapters (December 2021): HE for Good invites elaboration of those glimmers of alternative futures offered during the pandemic, those which foreground inclusion, equity, social justice, care and sustainability … [The book] will explore possibilities and critique with a purpose. It will offer ideas about the role of education in addressing “wicked” problems which need multiple solutions, resolutions, experiments, imaginaries. As in wider work towards social and climate justice, this book aims to answer the question: “What can be done”? It aims to foster hope and courage. Heterogeneity Our intention was not to produce one definitive stance in this book, but rather to work in coalition with other HE scholars and practitioners, globally, to create a blend of diverse choral voices addressing these key questions. Mindful of the dangers of the single story (Adichie 2009) and aware that the dominant discourses from the Global North are constructed as both homogenous and universal, we were clear in our commitment to heterogeneity and pluriversalism. From the moment that the call for chapters was shared, we worked to communicate with and invite participation from scholars (authors and reviewers) from many countries, with the aim of having representation from both the Global North and the Global South. Within regions and countries, we also hoped to break down hierarchies. Even for us, who have reasonably wide networks, this was not always straightforward, as we elaborate in a subsequent blog post. We also aimed for a mixture of established and emergent voices in the book. In addition to academics (educators and researchers) at all levels, we sought submissions from professionals (learning technologists, educational developers, etc.) as well as students, those in academic leadership positions, and educators working outside higher education but with valuable perspectives on it. Inclusion also extended to the selection of authors for the book’s forewords and afterwords (there are two of each). We wanted well known and well respected scholars, both internationally and regionally, noting that the latter may not have the global exposure they deserve. And we considered it essential to end the book with a young scholar looking to the/their future. Finding the right person involved reaching out to many people, because of course, scholars of the future are not yet well known. We are so grateful that each of the people we asked —outstanding scholars from Australia, Chile, India and South Africa— all said yes. An early decision in designing the book was that the modes of expression would be varied, i.e. chapter authors would not be limited to the constraints of traditional academic formats. In order to open up possibilities for the future, we invited authors to be creative and, thankfully, many authors accepted this challenge. In addition to chapters written in conventional forms, the book includes personal reflections, dialogues, poetry, an audio podcast, and a graphic story. We decided also at the outset that the book should include artwork, acknowledging the role of artists in “seeding resistance and providing the tools for us to imagine otherwise” (Davis et al., 2022, p. 8). In our search for existing openly licensed artwork, as well as extending invitations to artists to contribute new artwork, we prioritised artists from the Global South and women artists. We acknowledge and thank the authors of two recent publications that inspired us to imagine other-wise in crafting the form of Higher Education for Good: Teaching and Learning Futures: Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine Wilkinson, authors of All We Can Save: Truth, Courage and Solutions for the Climate Crisis (2020) and Angela Davis, Gina Dent, Erica Meiners and Beth Richie, authors of Abolition. Feminism. Now. (2022). Ethos of care HE4Good authors were experiencing, and often writing explicitly about, overload and exhaustion. As editors we took this seriously, especially when individuals faced difficulties and deadlines were delayed. In addition to general communications with authors, we tried to keep in touch personally with individual authors too. When authors of a few chapters had to drop out of the project, we did not, and could not, take it personally. We decided from the start that within a project schedule with tight deadlines, we would do all we could to prioritise care. This flexible approach applied to one another too. We kept ourselves to ambitious deadlines throughout, but during the project each of us got Covid and each had unexpected personal commitments. We alternated the workload but did not keep a tally. That kind of flexibility is based on mutual respect and trust. Seeding and contributing to a community What began as an idea shared by two people quickly grew to a project involving dozens of scholars after chapter proposals were accepted, authors began writing, and reviewers began engaging with authors’ work. Our intention and hope for the book to be more than a collection of chapters on a shared topic, but also a space to seed conversations and cross-fertilise ideas, soon became a reality. In a later blog we’ll describe in detail how this worked in practice. Our point here is that we actively opened the space of what the book could be to all authors and reviewers, inviting ideas for how individuals could meet, and encouraging contributors to think differently and to share their work with one another. In that sense, it is not simply a book, a product, but also a process and a contribution to a growing resistance movement in HE, where alternatives are being forged across the world. Final note The two of us have talked at length about how to write this post, and the posts to come. We believe it is important to share our editorial process because so much of what appears in the book is the result of that collective ethos of care. It certainly lifted us when things were difficult. And yet, it is not for us to say something glib about a particular practice like “this is essential” when we know that academic and professional HE working conditions are so deeply challenging and time-constrained. We can say that we aimed to enact the principles of heterogeneity, care and community through our editorial approach, mindful that it would be imperfect yet committed to trying hard. At the same time, we have to admit that this approach is time consuming, requires continual attention, and is not always easy. In the next blog post, we will talk about how we set about seeding a community of authors and reviewers. * Image from PickPick.com References Adichie, C. N. (2009). The danger of a single story [Video], TED Talk, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg Braidotti, R. (2020). “We” are in this together, but we are not one and the same. Bioethical Inquiry 17, 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10017-8 brown, a. m. (2017). Emergent Strategy. AK Press. https://www.akpress.org/emergentstrategy.html Czerniewicz, L., Agherdien, N., Badenhorst, J., et al. (2020). A wake-up call: Equity, inequality and Covid-19 emergency remote teaching and learning. Postdigital Science Education, 2, 946–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00187-4 Davis. A. Y., Dent, G., Meiners, E. R., & Richie, B. E. (2022). Abolition. Feminism. Now. Hamish Hamilton. Johnson, A. E., & Wilkinson, K. K. (2020). All We Can Save: Truth, Courage and Solutions for the Climate Crisis. One World. A friend’s son was recently awarded an ESRC PHD scholarship. I pointed out that this is a Very Big Deal, that these are competitive and hard to get and was greeted by surprised interest, not surprising really given that the friend is not in academia, the rules of which are at best opaque (the ESRC had itself been unknown).

Yes, let’s look up how rare this is, said I, turning to ChatGPT and asking what the success rates are for ESCR-funded PhD scholarships. I asked ChatGPT rather than my usual DuckDuckGo, because I suspected there would likely be several answers based on discipline etc. and that a synthesised summary would be useful. Immediate reply was provided - 14% with a URL to a named report even the page number 48. Seriously impressive! Before sending the link to my friend I thought I would check the report and clicked on the URL. Broken link. I told Chat GPT that the link did not work. Immediate reply with a correction. “I apologize for the confusion. Here is an updated link." Again, a broken link. Another corrected reply “I apologize for the error in my previous responses. Here is the correct link." Again, a broken link. “I apologize for the continued issues with the link. Here is an alternative way to access the information.” That does not work either. Never mind, I think, the ChatGPT database ends in 2021 so maybe that is why the dead links. At least I have the report’s name. So I search the old-fashioned way and eventually, I find the report and turn to Page 48. No relevant data at all, let alone a percentage of 14% or anything else. Next, I type into the box that I have found that report and the information is not there, and I need the relevant paragraph and an exact quotation. The ChatGPT reply says “I apologize for any confusion my previous responses may have caused. Upon double-checking the relevant report, I have discovered that there is no information regarding the success rate for ESRC-funded PhD research.” More apologies “I apologize for any inconvenience or confusion my earlier responses may have caused. If you have any further questions or concerns, please don't hesitate to let me know.” I won’t repeat the ongoing conversation, if that is what it was, because I boringly and doggedly pursued the question, intrigued to see whether a verifiable answer ever emerged. Ongoing made-up answers and continuing apologies. And no, never a verifiable answer. What to make of this? Obviously, to check everything. We know this. I know this. But I almost didn’t because it was such a sensible and likely source. Except it was entirely made up. As was eventually conceded (Upon double-checking the relevant report, I have discovered that there is no information regarding the success rate for ESRC-funded PhD research.”). It is intriguing that an answer was provided in the first place. I had also asked Perplexity and received an immediate response that it was not possible to provide the information. The other striking aspect was the human voice and tone. The first person “I” and the apologies. It really did feel like a real human exchange, but it really wasn’t one. Was it even a “real’ exchange? What is “real”? Once again, I know this. And yet….Also, why invent an answer? This adds a further human dimension of wanting to please. Any answer is better than disappointing the questioner. That is weird! Made up, and yet not lies exactly, I think, since lies do imply intent. Rather, two “hallucinations” in one: Generative AI pretending to be human and authoritatively and confidently making up information. As we say around here, Eish! * Image: "Hallucinations" by Sergio Cerrato - Italia from Pixabay Caption: Five-group classification of countries based on the localization rate of studies that mention a country name or demonym in their abstract. From Torres and Alburez-Gutierre (2022) Our paper looking at how educators understand the datafication and digitalisation of teaching and learning has just been published. ‘Technology is not created by the sky’: datafication and educator unease”, written by myself and Jennifer Feldman, explores datafication in education as well as educator agency. I hope it will be read because it gives voice to educators and makes what we think are important arguments about how datafication has inequitable manifestations and consequences in education. Also that educator responses are theoretically and pragmatically rationale even while so many are exploited by the dominant business models of big tech in education.

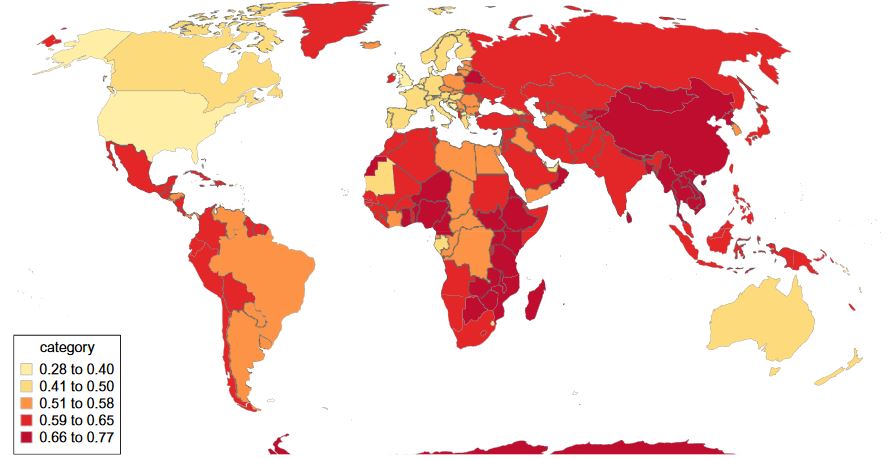

But I am not going to synthesise the paper here. I want to talk about something that happened in the peer review process, which is that one reviewer recommended – twice- that the country where the empirical study took place, and where the authors are located, should be mentioned in the title. The journal editors are in the UK, and the journal has an international readership. LMAT is known for astutely raising critical issues of international interest. We did not agree with this recommendation, because if we used our country in the title, we felt that this that it would signal that the issues were of local interest only, and less likely to be read. Fortunately, the LMAT editor agreed with us. Our instinct is backed by evidence. One study which analyzed research between 2004 and 2011 found publications with a country name systematically receive lower impact values both at the general level and by subject category (Abramo et al 2016). This is confirmed by another study which analysed a longer period, which found that mentioning a country in either the title or the abstract is associated with lower citation rates, and that this is observed for every country when all disciplines are combined (Archambault 2017). The findings are especially marked when comparing the global south and the global north. A 2022 study analyzed half a million social science research articles indexed between 1996 to 2020 finding that “empirical articles written by authors affiliated to institutions of the global North, using data from these countries, are less likely to include a concrete geographical reference in their titles. When authors are affiliated to global South institutions, and use evidence from global South countries, the names of these countries are more likely to be part of the article’s title”. We agree with the authors of the 2022 paper that evidence from and about the global north is assumed to be more universal. The assumption of a paper named as from the global south is probably that it is a case study, reflecting or exemplifying a local case, quite possibly of an issue described elsewhere as being relevant by researcher from the north. It is less likely to be regarded to be making a general point of broad interest. Yet, to return to the paper we published, we make a key argument about datafication and how it reflects, aligns with and contributes to inequality. Yes, this is a very South African concern given our sorry status as the country as having the worst inequality in the world of the countries measured, with a Gini coefficient score of 63.0. But is by no means a local issue, or even a global south issue. Many of the richest countries in the world suffer from severe inequality. According to the World Bank, the USA has a Gini coefficient of 41.4, the UK of 34.0, and Australia 34.4. (BTW the country with the lowest measured inequality in the world, Slovenia, has a score of 24.6 which is awful given that closest to zero is most equal). Inequality is a shockingly global phenomenon. It is not only a country level issue. Much research shows how within education sectors, institutions are stratified unequally, for example through inevitable rural/urban divides, and other considerations. Educators themselves within countries, regions and systems have unequal access, abilities to participate, and abilities to make choices. This is widely known. It is important to understand how new manifestations of inequality are asserting themselves, through emergent sociotechnical arrangements which shape education. Inequities play out and morph when educators and institutions engage with the forms of datafication expressed in dominant business models brought into the system in recent years by big tech. This point is illuminated by the educators interviewed for this research, building on research by colleagues in other countries. Those with less access to resources of all kinds (from technical to cultural capital to regulatory) are the ones most vulnerable to data exploitation. Which is why datafication in education is an equity issue. Everywhere. References Abramo, G., D'Angelo, C.A., Di Costa, F. (2016). The effect of a country's name in the title of a publication on its visibility and citability. Scientometrics, 109(3), 1895-1909 Archambault , AH; Sainte-Marie, AM; Larivière PMV (2017) On the citation gap of articles naming countries . Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics, Wuhan, 16-20 October 2017, 976-981. Torres, AFC and Alburez-Guteirrez,D (2022) North and South: Naming practices and the hidden dimension of global disparities in knowledge production in Fiske, S (ed) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 119 (10) e2119373119, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119373119 World Bank Gini Co-efficient by country 2023 , https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gini-coefficient-by-country  As are so many who are responding to the catastrophe that is Twitter, I am turning to blogging again. Just over two years ago, Catherine Cronin and I dreamt up an idea about imagining Higher Education For Good (#HEForGood). We were both disillusioned with HE and looking for ways to re-energise and find hope with our colleagues elsewhere. We put out a call for proposals which had an excellent response, culminating in a manuscript that is presently under review. We are both blown away when we look at what has been achieved in the last 18 months - 27 chapters by 74 authors in 18 countries. Including reviewers, people from 28 countries involved! We are having to be hold back our enthusiasm about sharing the stimulating and creative work that comprises the book. But we are able to - and have been - sharing the ideas that have crystallized from the work as well as from all the reading we have done. Catherine talked about these ideas at #OER23 in Scotland which she has blogged about here. I have been lucky recently to share these ideas in New Zealand. A big thank you to my generous hosts there: Kathryn MacCullum and Cheryl Brown from the University of Canterbury, Sean Sturm from Auckland University and Lucila Carvalho from Massey University. It was wonderful to actually be there physically, to engage in thoughtful conversations and to find how much the issues resonate across contexts. I am also chuffed that the recorded talks were used for teaching. While we can't yet describe the book in detail, from reflections, readings and the book chapters, Catherine and I can offer five tenets towards a Manifesto for Higher Education for Good. Tenet 1: Name and analyse the troubles of HE It very soon became clear to us that to look forward and reframe positive futures, it is essential to confront and stare into the darkness. This means (in summary) naming, understanding and analysing the central challenges of HE: neoliberalism both explicit and implicit; coloniality, manifested in so many ways; data extraction via myriad platforms; and multiple forms of inequality & exclusion. Tenet 2: Challenge assumptions and resist hegemonies The second tenet is that of resistance and the challenging of assumptions. This is about re-centering people and perspectives by bringing in voices and views from the margins. It is about border-crossings of several kinds including geographic, disciplinary, status and genre. And it is about resisting and and challenging dominant narratives of knowledge, technology, economics, society and culture. Tenet 3: Make claims for a just, humane and globally sustainable HE The third tenet is to stake and make firm claims for just, humane and globally sustainable HE. This means claiming and growing theories for good. It means making explicit claims for the values of justice and sustainability in a humane HE sector both now and in the future. Tenet 4: Courageously imagine and share fresh possibilities. The fourth tenet is to courageously imagine and share fresh possibilities. Here we call for the power and value of imagination in all forms, formats, methods, genres and approaches. Tenet 5: Make positive changes here and now And the fifth tenet is to make positive changes here and now, no matter what the size of them because change is contagious and because small streams become large rivers. Making change now can repair the past and create coalitions for the future. It is wonderful, and energising, to have started talking, sharing and engaging with colleagues and friends in various countries about ways of making hope and creating change. Looking forward to elaborating on these ideas, and on the fantastic chapters in the book as soon as feasibly possible! * Check here regularly for updates on #HEForGood, including links to presentations. In analogue photography there is a magical moment when something that was not visible becomes visible. There is a blank sheet of paper where an image develops slowly, emerges into being, something that was not there now comes to be there.

To get to that point, there are many steps, much expertise, a process of reviewing a roll of film to see which images are overexposed or underexposed and what is needed to bring the image into the best possible light. There are test strips and exposures of prints from different time periods to see which exposure works best for the crispest image. It is this process that is going through in my mind at the moment as the book Higher Education for Good (#HE4Good) is coming into existence. We are in the early stages now. The images are still being taken. But already in my mind’s eye the borders are starting to suggest themselves, dark clusters and absences, highlights and lowlights. This metaphor reaches its limits at this point because in photography a lone figure works in a dark room, whereas we are working in a collaborative darkroom bringing a collection of ideas into the light in the crispest possible way. The collaborative process is in full swing between ourselves as editors and at an early stage amongst the 64+ authors from 20+ countries who make up the book, talking synchronously within the constraints of time zones, existing commitments and academic strikes. Talking asynchronously thanks to technology. We are sharing ideas, threading concepts across chapters. We are capturing macro, meso and micro catalysts of change for good. We are recording forms of resistance to broken systems of Empire, platformisation, austerity while developing different images of the commons, the public good, justice, hope, care, sustainability, community and more. We will soon share the full chapter and author list. For now, a moment of excited anticipation. *Image from Dre Darkroom In Use 20 Aug 2011 Recently I asked on Twitter "Twitter friends, what are your best readings in digital inequalities, the digital divide and or digital inclusion?" There was lots of discussion and all sorts of interesting suggestions, which I list below. This is when social media is at its best - the power of weak ties!

Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani, @thatpsychprof: I’d recommend one of @hypervisible’s articles, for example: https://commonsense.org/education/articles/digital-redlining-access-and-privacy https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/ Maya "yes, that's really my last name" Hey, PhD @heymayahey: Perhaps a little more theoretical than desired, but I have really benefited from reading the work of Wendy Chun. Discriminating Data, but also earlier works such as Race and/as Technology. Su-Ming Khoo @sumingkhoo·: Old book but important https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/Zer/ Natalie B. Milman, Ph.D. @nataliebmilman; I have a digital folder & a few books - one I return to often is @markwarschauer 's piece - published in 2003: http://education.uci.edu/uploads/7/2/7/6/72769947/ddd.pdf (@markwarschauer I have good news—the book this is based on, Technology and Social Inclusion, will be released open access soon. Just finalizing the details now with MIT Press!) Dr. Stella Lee @stellal: I recommend anything by @ruha9 Especially Race After Technology. Michael Paskevicius @mpaskevic: I have found the research of Eszter Hargittai to be quite useful Gerrit Wissing @yokufunda: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3871423; https://technologyreview.com/2020/08/07/1006132/software-algorithms-proctoring-online-tests-ai-ethics/; https://theverge.com/2020/4/29/2123 Sandra Sinfield @Danceswithcloud: For Digital Inclusion I always turn to DS106 (https://ds106.us/about/) as a model of using the digital for creative purpose - and I follow @cogdog for ongoing uplift and inspiration. George Station @FirstYear156: I follow such as @ruha9, @safiyanoble, @hypervisible (which you do already, I know) and read what they're reading. Sometimes I gripe about EDUCAUSE proper, but @EDUCAUSEreview has good digital #DEI articles these days so kudos to their editors ✿Caroline Kühn✿ @carolak: This is an excellent one :-) The Promise of Access Technology, Inequality and the Political Economy of Hope By Daniel Green https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/promise-access and A digital new deal is also an excellent https://itforchange.net/digital-new-deal/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Digital-New-Deal-PDF.pdf Dr. Catherine Cronin @catherinecronin: https://whoseknowledge.org/ are wonderful. https://a4ai.org/meaningful-connectivity/ @A4A_Internet concept of 'meaningful connectivity' And this “reading next” pile: Well-being Freedom and Social Justice; Your Computer is On Fire; The Costs of Connection Julian McDougall @JulianMcDougall: Ellen Helsper’s The Digital Disconnect The Social Causes and Consequences of Digital Inequalities Dr Amanda M L Taylor (-Beswick) Digicritical @AMLTaylor66: Emily Keddell“Make Them Dance”: Shoshana Zuboff’s Surveillance Capitalism, Behavior Modification and Fraser’s “Abnormal Justice” * Thank you to Amanda Taylor-Beswick for the picture of her great books Recently Mandy Garner from University World News contacted me with a specific request to write something positive, particularly about how technology has improved access, enabled inclusion, that sort of thing. It was a challenge - how on earth to say anything positive about this past period in higher education, let alone about the role of technology?

This is what I came up with, hopefully managing to be both outraged and optimistic..... There is something rather tone-deaf about the aphorism, ‘Never let a good crisis go to waste’. If anything positive has come out of the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on higher education, it is surely despite the crisis, not because of it. It is also impossible to attribute anything much – let alone anything positive – to the ‘online pivot’ and its associated technologies. Firstly, the shift online has been only one factor among many that have been endured by students and academics over the past 18 months, including illness, death, family economic crises, change of responsibilities, change of modes, loss of educational communities and different pedagogies. These cannot be teased apart. Secondly, what has been called online learning has largely been emergency remote teaching and learning. Due to haste, deep fatigue, trauma, global unevenness and uncertainty about the future, there has been insufficient time for the considered planning needed for fully online programmes. Yet, somehow, some aspects of higher education have gone right, and, in the spirit of appreciative enquiry, it is worth articulating what these aspects might be. Now that inequality and inequity have been seen, they cannot be unseen Inequality is a social scourge, inevitably infiltrating higher education. It is almost a decade since former United States president Barack Obama described it as the most serious challenge of our time. Nothing has changed and, until COVID-19 hit globally, it became inescapable only when the entire higher education sector sent their students home. The pandemic made it impossible to ignore the inequalities hidden on residential campuses where connectivity and student residences appeared to level the playing field. Those brick-and-mortar spaces hid other forms of unequally distributed economic and cultural capital. The pandemic has made visible what should have never been ignored. Now that the impacts of inequality are clear and visible, they must never again be rendered unseen. The classroom has been made strange By shifting mode, academics and educators have had to look with fresh eyes at their learning environments; the classroom, as Shanali Govender describes it, has been made strange again. For many long-standing educators, the foundations of teaching had become opaque, lost in familiarity. While the initial panic saw a frantic rush to upload content in a bid to salvage the academic year, as the pandemic has inexorably worn on, it has become clearer what learning involves. Going online has made the supporting skeleton of pedagogy, of community and of curriculum explicit. Since the onset of the pandemic, attention has turned to rethinking time, reconceptualising space and learning environments, mapping pedagogy in new ways and reconsidering curricula. After the initial panic, online learning design has seen shifts to enabling interaction and designing new forms of assessment, challenging taken-for-granted practices and at times improving those historically practised in face-to-face teaching environments. Thus, while catalysed by the pandemic-induced pivot online, the fundamental issues of good teaching have received more sustained attention, no matter what the mode. Collaboration against the odds Universities are competitive institutions fostered by rankings and metrics that reflect a marketised culture of consumer choice. Research collaboration crosses borders deeply located in disciplinary knowledge. However, teaching is considered a solitary undertaking with academics rewarded in promotion criteria that privilege individualist behaviour. If anything, collaboration in the teaching space has been disincentivised. Yet, over the past 18 months, there have been myriad examples of informal mutual assistance. And at speed. Formal collaborative arrangements have sprung up and have been consolidated. This generosity is evident in the collection of examples crowdsourced by Alexandra Mihai showing the numerous inter-institutional partnerships in academic staff development. These include professional development courses designed across and for multiple institutions nationally and internationally, teaching and learning consortia and the creation of openly licensed toolkits and resource hubs. In short, the ‘not invented here’ barrier was broken, and that is surely something that has gone right. Rules got broken The higher education sector is notoriously slow to change. Despite there being hubs of innovation in different disciplines, universities at an institutional and often at a national level are governed by regulations designed to serve previous outmoded dispensations, many of which were on the way out even before the pandemic began. Rules were broken to prevent sectoral collapse: the multimodal approach to saving the year, combining analogue forms from paper, to radio and television – and digital forms including flash drives, pre-packaged tablets, mobile internet vans, cellphones and, of course, laptops with Wi-Fi. This has meant regulatory categories were understood as overlapping and categories of provision porous. Strictly demarcated rules specifying what is and isn’t distance education, what can or cannot receive state funding, what can or cannot be defined as ‘presence’, ‘hours spent together’, ‘hours in a classroom’ – these all got broken to save the academic year. And to save the life chances of students whose futures depend on the academic year being completed. Deeply imperfect as this has been, policy frameworks and the regulatory environment, usually glacially slow to change, were adjusted to protect institutions and for the greater good of students. This flexibility, made possible by breaking the rules, shows what is possible and what needs to continue. Addressing barriers and structural problems To go full circle, many of the persistent structural challenges shaping the higher education sector are now in plain sight and can no longer be wished away. Some of the fundamental socio-economic issues shaping the deep inequalities which characterise the higher education sector have started to receive attention. There has been recognition of how many students face enormous barriers to learning. The diversity of learning settings and their associated challenges have started to receive proper attention. Importantly, there has been a renewed emphasis on the importance of good teaching and the benefits of collaboration, both for equity and knowledge sharing. Leonard Cohen could have been talking about teaching offerings in his song "Anthem": Ring the bells that still can ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in. Last year 22 of us from 15 of South Africa’s 26 universities collaborated on a joint paper about the pandemic in South African universities, from an equity and inequality perspective. Many of us had never met one another but we all agreed that it was a serious issue which we could all contribute to from a range of context-specific experiences and varied perspectives. We think the paper was richer because of the multiple voices.

It was my wild idea but of course nothing would have happened without everyone’s enthusiastic participation. One of the co-authors, Matete Madiba, suggested we talk with her and colleagues at her university about collaborative writing. For us this was a positive experience, which is not automatically the case. These are the thoughts I shared…. Why write collaboratively?

Of course, there are different kinds of collaborative writing. In the first case, there is a shared issue which will be grappled with; the explicit aim is for the whole to be greater than the sum of its parts. There is a shared problem, probably with multiple sites. This works best when there is no intention to resolve the issue in the sense of coming up with a single solution, but to demonstrate complexity. In the case of our paper, it was consciously a process of collective meaning making. In the second case, there is a skeleton developed and a division of labour where different authors write different sections. A variant of this second option might involve an expert brought in to write specific sections. Some principles . Let’s not pretend. Collaborative writing is not a walk in the park. It makes a difference if there is a shared understanding. Here are some principles we have found useful.

Image: Faelle @deviantart CC 3.0 Turns out that announcing I am going to be blogging regularly has not made me blog regularly. So, this is an announcement that I am going to blog irregularly. Or continue to blog irregularly. I am still thinking about edtech as coloniality but of course I have been doing Other Things.

One of the Other Things I have been doing is writing an Insider’s Guide to Navigating the Research Bureaucracy at my university. You know, everything that you wished someone had told you? Turns out there is a lot to share about the informal systems as well as the formal ones. But that is not really blog worthy. Something else I did was write a piece on South Africa for the 2021 Educause Horizon Report. The brief was to describe higher education in South Africa especially in the light of the key trends identified by the Panel this year. That is on page 39 of the Report. What was striking is that Higher Education in South Africa represents an extreme case of a situation that the pandemic made clear is pretty much a global situation: inequality for students, for academics, for institutions, for national systems, for the sector as a whole. And how Covid has made everything so much more ingewikkeld - the dictionary says that means vexing and complicated. And how there is so much that needs to be better understood. Which is why I concluded the piece with a set of suggested research questions:

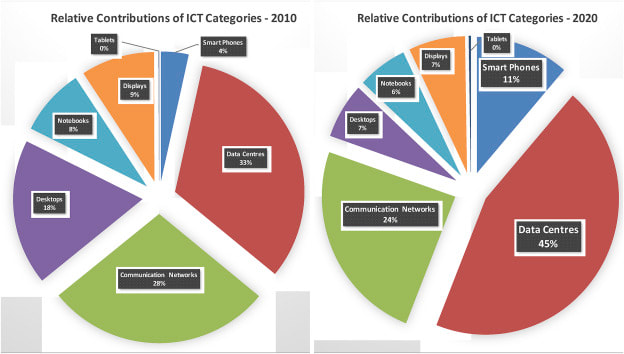

This blog is part of the section on coloniality and the exploitation of natural resources. This in itself is wide ranging, so this blog is very briefly about how those of us working in teaching and learning in digitally-mediated higher education can't really escape thinking about greenhouse emissions. The link between digital business models and climate change may be less obvious than other characteristics of coloniality. It was an area that I had an inkling about but once I explored it, I went down too many rabbit holes (many references!) to elaborate on in one blog post. During Covid there has been a fair amount of coverage about how lockdown has been good for the planet and how greenhouse emissions plummeted. Which is wonderful and has led to conjecture about how this might be sustained. At the same time, in Higher Education, there have been calls for increased investment in digital infrastructure, for a variety of reasons. While these seem commonsensical, they have to be made with an eye on the planet. Digitisation exploits mineral resources (which deserves a blog of its own) and it contributes to greenhouse emissions. One useful paper Assessing ICT global emissions footprint: Trends to 2040 & recommendations* (worth reading in full) studied the changes over ten years, summarised in these graphs. What is immediately noticeable is the growth of green house emissions from smart phones and from data centres (i.e. "the cloud"). Policy researchers such as Research ICT Africa argue that ubiquitous smart phone ownership is needed to overcome the digital divide. Analysts such as Gartner, and many others have underlined that HE information systems are moving into “the cloud”. So to overcome digital divides, and follow current trends, there is a danger of worsening green house emissions. A paradox? These trends combined with these graphs make a striking case for green energy in higher education digital infrastructure, highlighting that it is impossible to divorce the opportunities of the digital for teaching and learning (and higher education) from responsibilities to the planet *The study was undertaken pre-pandemic; I wonder what the situation looks like now? This 2nd blogpost on Calculating Coloniality dovetails beautifully with a request from AdvanceHE to present a short video provocation, available here, on the future of higher education, as part of a panel with Vasengelis Tsiligkrisis and Mark Burkin.

In the previous post, I argued that coloniality and current dominant extractive business systems both use technology for the primary purpose of profit making and market expansion. It is impossible to talk about the future without acknowledging that we are in the middle of a pandemic. What is interesting about Covid-19 is that while everyone recognises the horror and terrible impact of Covid19, in education the pandemic has also been described as an unanticipated and even exciting digital education experiment - indeed that the pandemic has been seen an opportunity to leapfrog into a digital future. I am worried about that digital future. I think that the pandemic has seen numerous practices which were already of concern pre-Covid, become entrenched, and that without intervention, 2030 will see higher education fully colonised by extractive technology-based business models. The word colonised has been used metaphorically by scholars (describing for example data colonialism or digital colonialism) yet strictly speaking denotes, as Maldonado-Torres (1) “political and economic relation in which the sovereignty of a nation or a people rests on the power of another nation” So, I prefer the term coloniality which, instead, he explains as “long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism, but that define culture, labor, intersubjective relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administrations”(1). The point is that such colonial ways of being have become normalised, they are acceptable ways of engagement and of treated as the default terms of relationships. And while they don’t take traditional historical forms of direct subjugation of one nation by another, fundamental patterns, behaviours and relations of power persist and are reinscribed today. New systems of extractive technology-based business models are an important vehicle for this reinscription, enabling the ultimate end goal of profit making and market expansions. While they hold out promises of progress, they require buy in to a system characterised by inherent inequalities, shaped by a homogenising world view and underpinned by new forms of exploitation. To talk about new forms of profit making and market -making in education, it is necessary to engage with the impacts of digitisation in society more generally. Unfortunately, so far, Higher Education is proving to be a mere subset of these broader extractive systems, unable as yet to provide robust alternatives as we are still in the early stages of imagining, researching and testing what these might be. Numerous scholars have described how technology is being appropriated and shaped by neoliberal systems. The culmination of this scholarship is provided in the detailed synthesising and analytical account of Zuboff’s work, on surveillance capitalism (2) which she succinctly describes as “a new economic order that claims human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction and sales”*. Interestingly she also describes it “as an expropriation of critical human rights that is best understood as a coup from above: an overthrow of people’s sovereignty”. It is striking how this loss of sovereignty is at the heart of the colonial project. Under colonialism individuals were themselves a form of capital through their labour, forced, indentured, and enslaved while their assets such local knowledge, land, natural resources fed the new economy. These relations persist, albeit rebranded under a contemporary veneer. But individuals now provide an additional form of capital: their data a powerful financialised asset (3)** exponentially growing in value through the collated minutiae of the total human experience- what people do, their habits and behaviours, where they are, the moves they make, the views they express and so on. The marketisation of HE has already become pervasive. Extractive business models are not limited to the big tech companies, they provide templates for businesses everywhere including in education. It is no co-incidence that there is currently increased investment in educational technology. Not only did the online pivot provide business opportunities, but ed tech companies are leveraging and experimenting with ways (described as innovative) of exploiting student data and experience for profit. The opportunities of the grand experiment afforded by the pandemic and of algorithmic academia has seen an annual investment growth rate of 16.3% expecting to reach $404 Billion by 2025 (4). The fact that so much of the technological infrastructural investment is being made by venture capitalists with their profit-making agendas is a cause for concern. For digital infrastructure to be fairly and equitably available, it needs to be a public good which public universities should be able to leverage. It is not simply the provenance but also the nature of that business model, premised on data extraction and financialisation which is especially worrying. People often understand this data to mean the extraction of private information (like a name or number) and while this is important, what is even more important is what companies originally called digital “exhaust” . This is where it turns out the value lies- in other words the content is less important than the metadata and the “ambient” data that digital services collect. This is what we listen to, where we linger, who we connect with, what we prefer, what we say in passing, what we ignore, the list goes on and on). This data is collected to build models which can both predict and influence, which can shape behaviour and thought. It is still early days to understanding this in society in general, and even earlier days in higher education. The marketised nature of universities has been recognised for decades, and the term academic capitalism has summed up how knowledge has come to be understood as a private commodity rather than a public good. Prior to Covid, the platform university exemplified the role of big tech companies and their practices shaping academia. What has been illuminated in recent times is how the pandemic has been a catalyst for the extension of surveillance capitalism into HE academia, as universities everywhere invested in services and platforms to service the over 200 million university students who “pivoted” hurriedly online. Relationships with companies such as Online Programme Managers have substantially increased (4) as well as with a whole range of companies providing unbundled services for the entire student journey – from student applications to online proctoring, as well as the student experience through learning analytics and the like. Even in the emergency rush online, the question of student data privacy has received some attention. In some universities and countries attention is being paid to the ownership of academic content through data privacy regulations and increasingly through data privacy positions. Much less attention is being paid to the “digital exhaust”, and to the control of extracted data. In contemporary business models, students are not owners of all their data; the risks are therefore considerable with student ambient data being consolidated into broader digital economic ecosystems. Even if the core data content is made private, the digital exhaust as an asset adds value. Let’s take Google for Education as an example. It offers a collection of tools to collaborate (Docs, Slides, Sheets, Drive, Jamboard) and communicate (Mail, Meet, Chat), for classroom management (Classroom, Assignments, Forms) and administration (Keep, Calendar). These tools are a subset of the larger Google ecosystem (think of Maps, Translate, Chrome, Youtube etc). The promise of easy integration is paid for by consolidated and manipulatable data sets of students who will become in future consumer citizens. Catch them young and they are hooked into the entire system for life. Through the shift to ERT, universities have delivered an entire generation of students to extractive business systems driven by profit seeking imperatives. There is no time now to talk about the co-operation between big tech companies, nor their special relationships with third parties, although there is evidence that this is exists. What is critical though in the Google example, is the centrality of Google search at the heart of the Google Alphabet behemoth. Prior to the pandemic, it was already understood how search played a gatekeeping role in knowledge formation. Google has over 90% of the search engine market and is so popular its brand has become for a synonym for search. A 2020 investigation (5) showed that a significant percentage of search results on Google search front page results point to Google’s own products- such as Youtube and others. If profit-making rather than relevance or neutrality determines which information is found online this has real implications both knowledge comprehension and for knowledge creation. It is significant that it is a decolonial scholar, Mbembe (6) , who has warned of knowledge systems worldwide being underpinned by the logic of value extraction (6) thus subverting the knowledge agenda. I will end where I began - with coloniality. Maldonado-Torres reminds us, as modern subjects we breathe coloniality all the time and every day. What this means is that these extractive practices are not outside of us as citizens, as educators, as academics and as students. We are participants and we have responsibilities. In short, extractive economic systems are shaping the future of education and unless policymakers and knowledge makers act soon, fast mutating forms of coloniality will be imprinted in the DNA shaping the future of the university and the higher education sector. References

*In an interview 9 Harvard professor says surveillance capitalism is undermining democracy – Harvard Gazette) , Zuboff stresses that although it was Google that first learned how to capture surplus behavioral data, more than what they needed for services, and used it to compute prediction products that they could sell to their business customers, in this case advertisers, surveillance capitalism is no more restricted to that initial context than, for example, mass production was restricted to the fabrication of Model T’s. In other words, it is this model which provides a template which is being explored and exploited in higher education. ** Komljenovic makes a compelling argument for digital data to be understood as assets rather than commodities, for reasons more complex than it is possible to summarise here. Best to read her excellent article. This is the first of a series of blog posts for thinking aloud about coloniality as it is being enacted through tech-based extractive business models and new forms of sovereignty. The title has triple resonances for me- calculating as in ‘working out or making sense of”, calculating as in cunning and calculating as in the numerical basis of new forms of digital society and digital education.

Digital colonialism and data colonialism are terms which have some currency at present. I have heard them used in the fields of education, sociology, computer science and elsewhere. They are sometimes used metaphorically and sometimes to refer to big US tech companies. I was intrigued when the prominent decolonial scholar Achille Mbembe commented that the world has become a data emporium, a vast field of data awaiting exploitation, of predatory extractive forces, which can be seen as part of ongoing histories of colonisation. This signals a confluence of thinking from different domains. Strictly speaking colonialism refers to the sovereignty of one nation over another, literally of one territory over another. Yet the term is more than simply symbolic or metaphorical. The term coloniality strikes as more apt as Maldonado-Torres describes it: “long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism, but that define culture, labor, intersubjective relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administrations”. It is the systems, practices and patterns of power that echo and repeat colonial forms of engagement. They have become the default terms of relationships and have become internalised, normal and indeed the default. During the pandemic, which both critics and evangelists have described as a global educational experiment, I have been especially interested in how coloniality is playing in Higher Education. Thinking about this means considering how the characteristics of coloniality play out in society generally, given that, at present, Higher Education is a subset of these practices, rather than a challenge to them. The key ongoing colonial characteristics which echo historically, and which are being re-enacted and reinscribed now are as follows.

That is the taster! I have loads of notes and examples (thank you Evernote), and writing the blog posts will make me concisely articulate what each of these characteristics or categories would look like, and how they should be refined. The next post will be about profit making and market expansion. A new year, a new resolution. Mine this year includes to start blogging again (the others are not for public consumption!). I have been an intermittent blogger, even at a times a regular blogger (well quite a while ago now), and sometimes a guest blogger. Also various articles in publications including The Conversation, World University News and Educause Review. Now starting again on my own site, and keeping it simple, just to get going again. Let's hope 2021 does not throw us too many curved balls. Image thanks to Tim Mossholder, Unsplash

|

AuthorI am a professor at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, interested in the digitally-mediated changes in society and specifically in higher education, largely through an inequality lens Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed