|

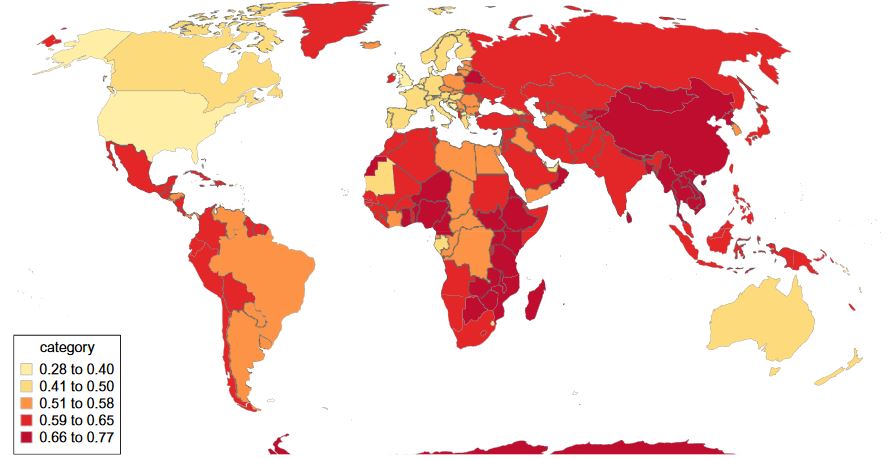

Caption: Five-group classification of countries based on the localization rate of studies that mention a country name or demonym in their abstract. From Torres and Alburez-Gutierre (2022) Our paper looking at how educators understand the datafication and digitalisation of teaching and learning has just been published. ‘Technology is not created by the sky’: datafication and educator unease”, written by myself and Jennifer Feldman, explores datafication in education as well as educator agency. I hope it will be read because it gives voice to educators and makes what we think are important arguments about how datafication has inequitable manifestations and consequences in education. Also that educator responses are theoretically and pragmatically rationale even while so many are exploited by the dominant business models of big tech in education.

But I am not going to synthesise the paper here. I want to talk about something that happened in the peer review process, which is that one reviewer recommended – twice- that the country where the empirical study took place, and where the authors are located, should be mentioned in the title. The journal editors are in the UK, and the journal has an international readership. LMAT is known for astutely raising critical issues of international interest. We did not agree with this recommendation, because if we used our country in the title, we felt that this that it would signal that the issues were of local interest only, and less likely to be read. Fortunately, the LMAT editor agreed with us. Our instinct is backed by evidence. One study which analyzed research between 2004 and 2011 found publications with a country name systematically receive lower impact values both at the general level and by subject category (Abramo et al 2016). This is confirmed by another study which analysed a longer period, which found that mentioning a country in either the title or the abstract is associated with lower citation rates, and that this is observed for every country when all disciplines are combined (Archambault 2017). The findings are especially marked when comparing the global south and the global north. A 2022 study analyzed half a million social science research articles indexed between 1996 to 2020 finding that “empirical articles written by authors affiliated to institutions of the global North, using data from these countries, are less likely to include a concrete geographical reference in their titles. When authors are affiliated to global South institutions, and use evidence from global South countries, the names of these countries are more likely to be part of the article’s title”. We agree with the authors of the 2022 paper that evidence from and about the global north is assumed to be more universal. The assumption of a paper named as from the global south is probably that it is a case study, reflecting or exemplifying a local case, quite possibly of an issue described elsewhere as being relevant by researcher from the north. It is less likely to be regarded to be making a general point of broad interest. Yet, to return to the paper we published, we make a key argument about datafication and how it reflects, aligns with and contributes to inequality. Yes, this is a very South African concern given our sorry status as the country as having the worst inequality in the world of the countries measured, with a Gini coefficient score of 63.0. But is by no means a local issue, or even a global south issue. Many of the richest countries in the world suffer from severe inequality. According to the World Bank, the USA has a Gini coefficient of 41.4, the UK of 34.0, and Australia 34.4. (BTW the country with the lowest measured inequality in the world, Slovenia, has a score of 24.6 which is awful given that closest to zero is most equal). Inequality is a shockingly global phenomenon. It is not only a country level issue. Much research shows how within education sectors, institutions are stratified unequally, for example through inevitable rural/urban divides, and other considerations. Educators themselves within countries, regions and systems have unequal access, abilities to participate, and abilities to make choices. This is widely known. It is important to understand how new manifestations of inequality are asserting themselves, through emergent sociotechnical arrangements which shape education. Inequities play out and morph when educators and institutions engage with the forms of datafication expressed in dominant business models brought into the system in recent years by big tech. This point is illuminated by the educators interviewed for this research, building on research by colleagues in other countries. Those with less access to resources of all kinds (from technical to cultural capital to regulatory) are the ones most vulnerable to data exploitation. Which is why datafication in education is an equity issue. Everywhere. References Abramo, G., D'Angelo, C.A., Di Costa, F. (2016). The effect of a country's name in the title of a publication on its visibility and citability. Scientometrics, 109(3), 1895-1909 Archambault , AH; Sainte-Marie, AM; Larivière PMV (2017) On the citation gap of articles naming countries . Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics, Wuhan, 16-20 October 2017, 976-981. Torres, AFC and Alburez-Guteirrez,D (2022) North and South: Naming practices and the hidden dimension of global disparities in knowledge production in Fiske, S (ed) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 119 (10) e2119373119, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119373119 World Bank Gini Co-efficient by country 2023 , https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gini-coefficient-by-country

0 Comments

As are so many who are responding to the catastrophe that is Twitter, I am turning to blogging again. Just over two years ago, Catherine Cronin and I dreamt up an idea about imagining Higher Education For Good (#HEForGood). We were both disillusioned with HE and looking for ways to re-energise and find hope with our colleagues elsewhere. We put out a call for proposals which had an excellent response, culminating in a manuscript that is presently under review. We are both blown away when we look at what has been achieved in the last 18 months - 27 chapters by 74 authors in 18 countries. Including reviewers, people from 28 countries involved! We are having to be hold back our enthusiasm about sharing the stimulating and creative work that comprises the book. But we are able to - and have been - sharing the ideas that have crystallized from the work as well as from all the reading we have done. Catherine talked about these ideas at #OER23 in Scotland which she has blogged about here. I have been lucky recently to share these ideas in New Zealand. A big thank you to my generous hosts there: Kathryn MacCullum and Cheryl Brown from the University of Canterbury, Sean Sturm from Auckland University and Lucila Carvalho from Massey University. It was wonderful to actually be there physically, to engage in thoughtful conversations and to find how much the issues resonate across contexts. I am also chuffed that the recorded talks were used for teaching. While we can't yet describe the book in detail, from reflections, readings and the book chapters, Catherine and I can offer five tenets towards a Manifesto for Higher Education for Good. Tenet 1: Name and analyse the troubles of HE It very soon became clear to us that to look forward and reframe positive futures, it is essential to confront and stare into the darkness. This means (in summary) naming, understanding and analysing the central challenges of HE: neoliberalism both explicit and implicit; coloniality, manifested in so many ways; data extraction via myriad platforms; and multiple forms of inequality & exclusion. Tenet 2: Challenge assumptions and resist hegemonies The second tenet is that of resistance and the challenging of assumptions. This is about re-centering people and perspectives by bringing in voices and views from the margins. It is about border-crossings of several kinds including geographic, disciplinary, status and genre. And it is about resisting and and challenging dominant narratives of knowledge, technology, economics, society and culture. Tenet 3: Make claims for a just, humane and globally sustainable HE The third tenet is to stake and make firm claims for just, humane and globally sustainable HE. This means claiming and growing theories for good. It means making explicit claims for the values of justice and sustainability in a humane HE sector both now and in the future. Tenet 4: Courageously imagine and share fresh possibilities. The fourth tenet is to courageously imagine and share fresh possibilities. Here we call for the power and value of imagination in all forms, formats, methods, genres and approaches. Tenet 5: Make positive changes here and now And the fifth tenet is to make positive changes here and now, no matter what the size of them because change is contagious and because small streams become large rivers. Making change now can repair the past and create coalitions for the future. It is wonderful, and energising, to have started talking, sharing and engaging with colleagues and friends in various countries about ways of making hope and creating change. Looking forward to elaborating on these ideas, and on the fantastic chapters in the book as soon as feasibly possible! * Check here regularly for updates on #HEForGood, including links to presentations. |

AuthorI am a professor at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, interested in the digitally-mediated changes in society and specifically in higher education, largely through an inequality lens Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed